November 18, 2015

Leaky Ships: Ocean Carriers in the Age of Profitless Shipping

Tags:

Leaky Ships: Ocean Carriers in the Age of Profitless Shipping

“Should you find yourself in a chronically-leaking boat, energy devoted to changing vessels is likely to be more productive than energy devoted to patching leaks.” – Warren Buffett

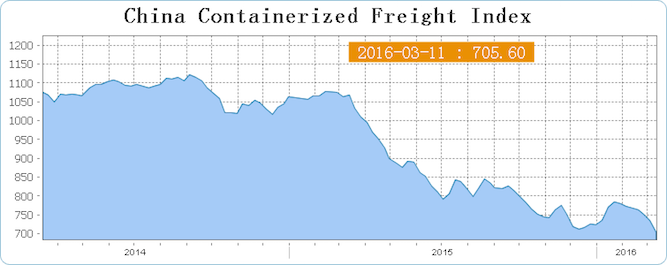

Global shipping rates are astonishingly low right now; it’s possibly never been cheaper to ship goods around the world, ever. The China Containerized Freight Index has been going lower and lower.

Source: Shanghai Shipping Exchange

As of March 2016, it costs around $400 to move a 40-foot container from Shenzhen to Rotterdam, which is barely enough to cover the cost of fuel, handling, and Suez Canal fees. Here’s some more context. Let’s say that you want to travel for a year; it’s cheaper to put your personal belongings in a shipping container as it sails around the world than to keep it at a local mini-storage facility.

No ocean carrier can earn returns above its cost of capital at these price levels.

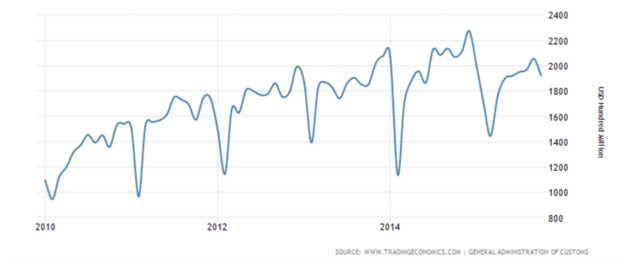

A slowdown in demand has contributed to this price collapse, but it can’t entirely explain record low freight prices. In spite of a very real downturn in Chinese exports, trade volumes remain higher than just a few years ago, when container shipping prices were relatively high.

Chinese Export Volumes (in 100M USD):

Source: TradingEconomics.com

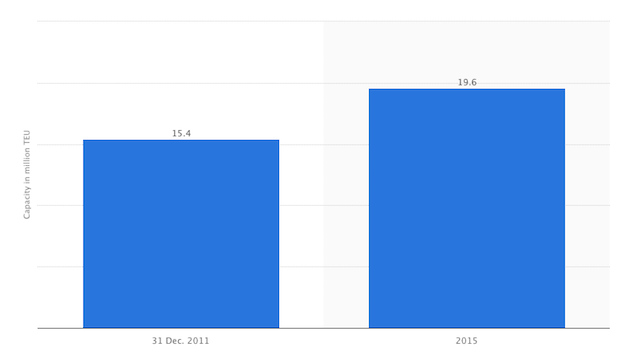

Instead, the collapse in prices is mostly driven by overinvestment in shipping capacity by ocean carriers. The newest generations of container ships are larger and so much more efficient than previous ships. Lower costs matter in commodified industries like freight shipping, and it’s no surprise that global container lines have aggressively upgraded their fleets.

It takes about three years to build and outfit a container megaship. And it was three years ago that the many carrier lines decided to invest in larger ships, when freight prices were near a historic high. At the time, carriers expected freight prices to be high and global trade to be growing quickly. That turned out not to be the case, and now there’s much greater supply.

Capacity of global container ship fleet, a comparison between 2011 and 2015 (in million TEU)

Source: Statista.com

The expected profits from more efficient ships has never materialized. As every shipping line made similar investments, they drove down the baseline market price, competing profits away. It’s been a classic arms race. To make matters worse, not only have carriers not made profits, they’ve found themselves burdened with enormous loads of debt and anemic rates of return.

The problem is likely to get worse before it gets better. The Boston Consulting Group previously said that it anticipates a 30% increase in container shipping capacity by 2019. Maersk has now announced that it will cancel orders for its last six Triple-E class ships. Furthermore, barring some unforeseen economic miracle, global trade is unlikely to grow at a rate to keep up.

Some carriers have diversified into higher-margin industries, such as port terminal operations, offshore oil development, supply chain management, and marine maintenance services. But for those that haven’t diversified outside their industry, it’s likely too late now. There’s no reason to think they will be better at buying or starting businesses than their investors, and many reasons to think they will be worse.

The New Economics of Container Ships

How can ocean carriers hope to sustain themselves in a world where supply outstrips demand, driving prices to levels where no company can earn returns?

The capacity investments by larger companies are hardball moves against smaller, weaker competitors. The best-run carriers have used their balance sheets and access to capital to invest in lower cost positions—that is, doubling down on ever larger fleets. Larger carriers benefit from economies of scale in purchasing, ship maintenance, and other aspects of operations. Spreading those expenses across larger volumes lowers average costs, and gives them a superior pricing position. The operators of smaller lines are already finding it more difficult to succeed in this environment. Rolf Habben Jansen, CEO of mid-sized carrier Hapag-Lloyd said recently, “Rates must go up. We have too many trades where we are moving cargo below operating cost.”

To further their scale position, the two largest ocean carriers, Maersk and MSC, have formed an alliance known as the M2 to advance their leadership position. CMA CGM, China Shipping, COSCO, and UASC have followed through with an alliance of their own. Alliances make it possible to have sufficient sailings by sharing vessels, though they don’t have quite the scale advantages of a single massive carrier acting alone. Still, when an alliance coordinates activities to set prices on their core tradelanes, there’s little reason for other carriers to go lower. In the long run there’s no way for the other companies to compete with the alliances on price, as their superior scale gives them lower average costs.

That’s how the leading carriers have traditionally been able to create a price umbrella, where they coordinate efforts to maintain prices at a level where they can earn profits. However, the recent race to invest in capacity has driven supply to such a level that such coordination has become difficult, and is intensifying pressure on smaller companies to be absorbed through M&A. Consolidation would increase economies of scale, giving companies further cost advantages. And with enough market power, they’ll be able to reduce capacity to prop up prices.

Although we’ve seen several carrier alliances and a handful of acquisitions, other efforts at consolidation have been blocked by governments, which see flagship carriers as serving important national interests. Many ocean liners are state-owned enterprises, while many others are owned by families with long investment horizons and motives that are not purely economic.

It’s uncertain how all of this will resolve. In any case, both consumers and retailers are benefiting from lower shipping prices. Global trade is one of the great forces for good in the world, and cheap freight will lead to more of it.

Read this next >> A Guide to the Largest Ocean Carriers in the World

About the Author